Postal Voting in German Elections

Abstract

This study analyzes postal voting in Bundestag elections using official electoral statistics of the Federal Republic of Germany. It examines differences between postal and in-person voting results, regional variations in postal voting patterns, and the impact of postal voting and turnout on political preferences of voters in Germany. Findings indicate postal voting is disproportionately used by supporters of "traditional" parties (CDU/CSU, SPD, the Greens), while being less common among voters of AfD and The Left. The paper proposes a methodology for analyzing turnout-based electoral metrics, accounting for postal precincts, which constitute 30% of all election commissions at the lower level, and which lack a preliminary electoral roll. The study demonstrates that Germany's turnout distribution follows a near-unimodal pattern, and party vote distributions across turnout levels show significant variation.

Introduction

Postal voting has been a long-standing German electoral tradition. In the 2025 Bundestag election, 37% of voters cast their ballots by mail. Russian critics of foreign electoral systems frequently rebuke German elections for this practice, alleging that postal voting is highly susceptible to fraud. Occasionally, our "critics of bourgeois theory" confuse postal voting with "early voting" — a misconception arising from the fact that postal ballots can indeed be submitted prior to election day, not only via mail but also at designated drop-off points for "postal ballots". Recently, for obvious reasons, postal voting has increasingly been compared to remote electronic voting.

These criticisms stem from a "Russia-centric" view of elections and from traditions of early voting fraud that have persisted in Russian elections (and, incidentally, in Belarusian ones as well). Although early voting was abolished in Russia's federal and regional elections in 2002 (we are excluding exceptional cases of early voting in remote areas), it remained in use in local elections until 2010. After being abolished completely, it was reinstated in 2014 and has since been exploited by unscrupulous political technologists to give the "preferred" candidate a not particularly legal boost. Where early vote returns could be counted separately, they typically showed statistically significant deviations from election-day returns [4; 5; 6]. In Russia, early voter mobilization was achieved either through bribery (less frequently) or administrative coercion (more commonly).

Postal voting saw minimal use in Russia despite being legally permitted in certain federal subjects (Sverdlovsk, Yaroslavl, Tyumen, and Murmansk Oblasts, as well as Saint Petersburg) [10].

Beyond criticism from Russian experts, postal voting has faced intense scrutiny in the United States, particularly following the 2020 and 2022 elections [2; 11]. In Germany, however, we find no evidence of complaints about postal voting despite its growing prevalence.

This raises a question of whether Germany's postal voting system distorts true voter preferences. How does it affect election results and turnout rates? In this study, we address these questions using Germany's electoral statistics. Fortunately, the statistical data are both highly detailed and publicly accessible.

Historical statistics of postal voting

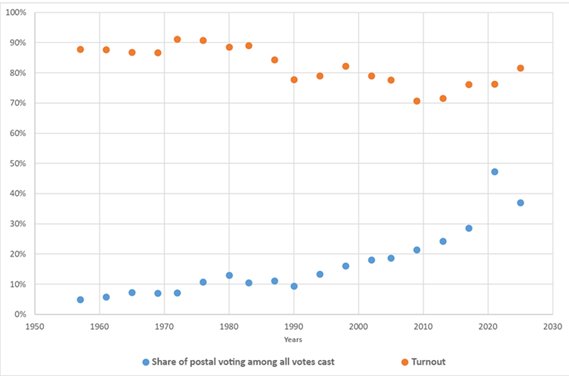

Statistical data on postal voting in Bundestag [1] elections, now including 2025 results [3], demonstrates its gradual expansion in Germany. Figure 1 also shows the voter turnout rate (voting in Germany is voluntary). The general trend demonstrates a gradual increase in the share of postal voting while maintaining relatively stable turnout levels. Therefore, the share of postal voting has practically no effect on voter turnout.

It is worth noting that in 1990, Germany underwent significant changes: five states (Thuringia, Saxony-Anhalt, Saxony, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, and Brandenburg — hereafter referred to as the "eastern states") previously part of the GDR were incorporated into the FRG. The total number of eligible voters in the 1990 Bundestag election increased to 60,436,560 (compared to 45,327,982 in 1987). Figure 1 reveals that overall turnout declined (with eastern states voting less actively than western ones), while the share of postal voting remained virtually unchanged.

Figure 1. Turnout rates and postal voting shares in FRG Bundestag elections since 1957.

Regional variations in turnout and postal voting

Germans have gradually adapted to postal voting: in 1994, the average share of postal voting was 8.4% in eastern states and 14.9% in western states. By 2025, these figures reached 29.8% and 37.3% in eastern and western states, respectively (when calculating postal voting share by dividing mailed ballots by total votes cast, the 2025 Bundestag election shows 28.9% for eastern states and 38.6% for western states).

A similar pattern holds for voter turnout: on average, it remains lower in eastern states than in western ones. From 1990 to 2025, average turnout stood at 72.2% across eastern states, 75.4% in Berlin, and 77.6% in western states. An interesting observation emerges: national turnout level dropped following German reunification and has yet to go back to pre-unification levels. At the same time, the number of parties actually participating in elections and getting a seat in parliament is growing.

Invalid ballots in postal and in-person voting

The share of invalid ballots in German elections remains remarkably low. In the 2025 Bundestag election, invalid second votes (i.e., votes for party lists) ranged from 0.78% in Saxony-Anhalt to 0.31% in Bavaria, with a national average of 0.56%. The rate is slightly higher for first votes (cast for candidates in single-seat constituencies), averaging 0.85% nationwide. This pattern has persisted since at least 1957, though the overall rate of invalid votes has gradually declined over time.

A striking observation is that all German states show higher rates of invalid ballots during in-person voting compared to postal voting. This strongly supports the hypothesis that postal voting reflects more deliberate and conservative voting behavior than in-person participation.

Political preferences in postal and in-person voting

Comparing the political preferences of postal and in-person voters reveals significant and consistent cross-state difference for only one party — the AfD. For more traditional parties, these variations are similarly uniform across all states. The Left Party (which won 8.8% in the 2025 election) constitutes an exception. This party's postal vs. in-person voting gap diverges depending on the state: postal voting was stronger in eastern states, while in-person voting was stronger in western ones.

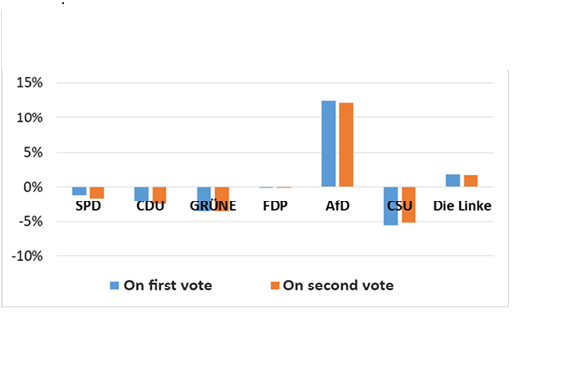

Figure 2 displays the differentials between in-person and postal voting shares across Germany for all seven major parties (while formally two separate parties, the CDU and CSU are considered as one in this case, as the CSU effectively operates as the CDU's Bavarian branch). Six of these parties secured parliamentary seats. The Free Democratic Party (FDP) received only 4.3% of second votes, failing to clear the electoral threshold; one seat was given to the SSW minority party under special constitutional provisions. The figure presents differentials for both first and second votes; these differentials are not significantly different from each other.

Figure 2. Difference in vote shares between in-person and postal voting.

When one examines this figure without assuming systematic pro-establishment bias in postal voting across all states, one can notice a clear pattern: supporters of opposition parties (AfD and The Left) exhibit stronger preferences for in-person voting compared to supporters of traditional parties (those previously in governing coalitions) and current incumbents.

Notably, this trend held equally true in Bundestag elections both eight and four years ago [4; 8; 9].

Turnout for different types of voting

A more nuanced analysis of electoral impact of postal voting can be conducted using precinct-level data. For the 2025 Bundestag election, 95,111 precinct election commissions were established. There were three types of said commissions: regular (66,465), postal (28,643), special (3) (calculated based on [7].

Originally, all voters are entered into the lists of regular precinct election commissions in advance (in exceptional cases, a voter may be added to the list up until election day). In this election, the total number of voters on the electoral roll was 60,510,631. All voters entered in the list in advance are mailed a proposal to obtain a voting certificate (Wahlschein) from their regular precinct commission, enabling them to either vote by mail or to have the option of voting at any polling station in their constituency on election day. German voters use the latter option extremely rarely: only 0.33% of participating voters utilized this opportunity in the election under consideration.

The remaining voters who have expressed a desire to receive a voting certificate use it to vote by mail. At the same time, 94.4% of voters who received a voting certificate do indeed vote by mail (the rest do not use their received voting certificate for some reason). Therefore, "turnout" for postal voting is extremely high and not particularly diverse (incidentally, the same is true for remote e-voting in Russia). This suggests that analytical methods that rely on distribution of electoral indicators by turnout cannot apply to postal voting.

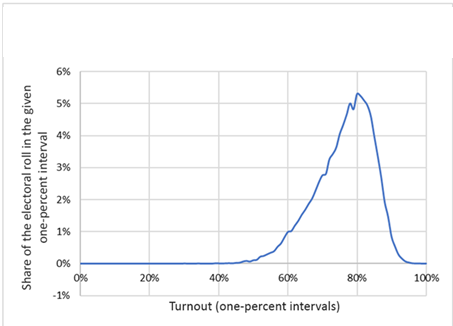

Voters who did not request a voting certificate retain the option to cast a paper ballot at a regular polling station on election day. Nationwide turnout at regular polling stations during the 2025 Bundestag election stood at 76.8%. The distribution of registered voters by turnout at regular polling stations is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Electoral roll distribution by turnout for regular polling stations.

Distribution of votes depending on turnout

The distribution of political preferences by turnout at postal polling stations where participation is clustered near the maximum is not analytically meaningful. However, this distribution can be analyzed if postal stations are merged with their assigned in-person polling stations. Data on these assigned polling stations can be obtained (though not without difficulty) from Germany’s nationwide electoral statistics that were published on April 30 (34 days after election day) by the Federal Returning Officer [7].

Unfortunately, the official statistics do not specify which postal polling station a specific in-person polling station is assigned to. The decision to assign a voter to a specific postal polling station is made by constituency or state election organizers after receiving confirmation from the voter that they wish to obtain a voting certificate. The official statistics only assign regular polling stations to certain administrative units (Verbandsgemeinde), to which specific postal voting stations are also assigned. Moving forward, we will refer to these Verbandsgemeinde as "municipal associations" (MA). Municipal association assignment and numbering rules are sufficiently complex on their own, but the delegation of these tasks to state officials (rather than federal ones) means implementation varies based on personal interpretation.

Within a single electoral constituency (of which there were 299 in the 2025 Bundestag election), the number of MAs ranges from one to as many as 136 (in Berlin's constituency No. 80). Each MA may contain between one and 241 regular precinct election commissions and between one and 211 postal-voting commissions.

Therefore, a voter registered in a specific in-person polling station may vote at one of the postal voting stations (assigned to them by constituency or state election administrators) within their MA.

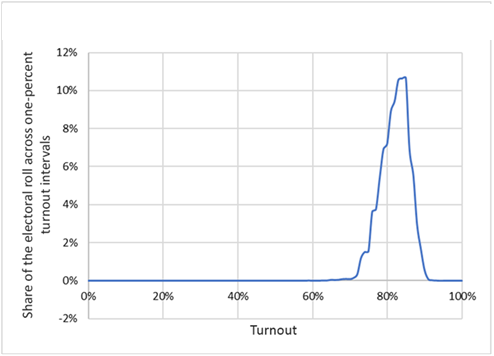

All electoral characteristics can be calculated for each MA, including the turnout distribution of its registered voters and their political preferences. In total, we identified 5,319 municipal associations in the 2025 Bundestag election. The turnout distribution of registered voters is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Distribution of MA electoral rolls by turnout.

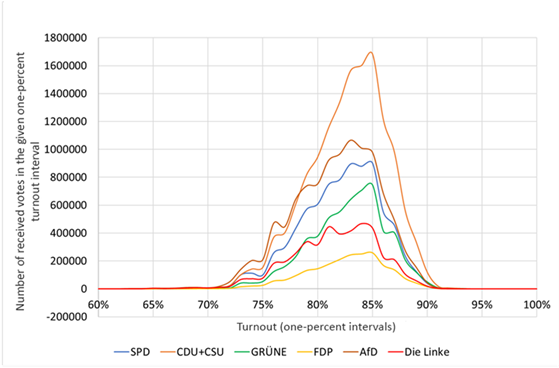

The distribution of votes cast for parties across turnout intervals (Spilkin diagrams) is of particular analytical interest. As shown in Figure 5, different parties gained votes differently across various turnout intervals (meaning no uniform distribution pattern among all parties except one was revealed, unlike what is typically observed in Russian elections).

Figure 5. Shpilkin diagram

In general, the dependence of political preferences on both turnout levels and the proportion of postal voting can be characterized by correlations between each party's vote share and the corresponding electoral indicator. That said, these indicator sequences should be compiled at the municipal association level rather than for regular commissions.

These correlations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Correlations between the shares of votes received by parties and turnout indicators

| Correlations Indicator sequence/Party sequence | SPD | CDU+CSU | GRÜNE | FDP | AfD | Die Linke |

| Total turnout | -0.06 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 0.34 | -0.27 | -0.38 |

| Turnout at regular PECs | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.35 | -0.17 | -0.22 |

| Share of postal voters | -0.25 | 0.52 | 0.25 | 0.09 | -0.43 | -0.14 |

| Ratio of regular voters to postal voters | 0.13 | -0.43 | -0.35 | -0.16 | 0.52 | 0.05 |

Naturally, the last two rows of this table show opposite signs.

Of particular interest is the comparison between the first and second rows. The "traditional" parties (Greens and FDP) increase their vote share when turnout increases. That said, this increase is equally strong for both in-person and postal voting. The vote share for another "traditional" party, the CDU/CSU bloc, also increases following increased turnout, and postal voting contributes more significantly to this increase. For Germany's Social Democratic Party (SPD), the turnout-result correlation is weaker overall and shows opposite signs between regular and postal voting precincts. The negative correlations for "opposition" parties (AfD and The Left) indicate they fall behind in high-turnout municipal associations, and their losses grow proportionally to the share of postal voting.

This table is consistent with the conclusions drawn from Figure 2.

Received 13.05.2025, revision received 16.05.2025.

References

- Anteil der Briefwählenden bei den Bundestagswahlen 1994 bis 2025 nach Ländern. – Bundeswahlleiterin. URL: https://www.bundeswahlleiterin.de/dam/jcr/e480be53-58bf-45b1-a860-711fbb7eaf7f/btw_1994bis2025_briefwahl.pdf (accessed 17 May 2025). (In Ger.) - https://www.bundeswahlleiterin.de/dam/jcr/e480be53-58bf-45b1-a860-711fbb7eaf7f/btw_1994bis2025_briefwahl.pdf

- Brikulsky I.A. The US Constitution and Postal Voting: Why Did Trump Turn Out to Be Right? – Electoral Politics. 2022. No. 2 (8). P. 4. - https://electoralpolitics.org/en/articles/konstitutsiia-ssha-i-pochtovoe-golosovanie-pochemu-tramp-okazalsia-prav/

- Bundestagswahl 2025 – Brief Urne Stimmabgabe nach Ländern. – Bundeswahlleiterin. URL: https://www.bundeswahlleiterin.de/dam/jcr/a4d5c812-9ba1-45ce-8a66-62ea4e974dac/btw25_ergebnisse_bezirksart.pdf (accessed 17.05.2025). (In Ger.) - https://www.bundeswahlleiterin.de/dam/jcr/a4d5c812-9ba1-45ce-8a66-62ea4e974dac/btw25_ergebnisse_bezirksart.pdf

- Buzin A. Etyd o dosrochnom golosovanii v Rossii i Germanii [A Study of Early Voting in Russia and Germany]. – Andrei Buzin's LiveJournal, 30.09.2017. URL: https://abuzin.livejournal.com/166905.html (accessed 17.05.2025). (In Russ.) - https://abuzin.livejournal.com/166905.html

- Buzin A.Yu. Chto bylo na dosrochnom golosovanii? [What Went On During Early Voting?] – Website of Interregional Voter Association, 05.07.2020. URL: http://www.votas.ru/DosrochkaOG.html (accessed 17.05.2025). (In Russ.) - http://www.votas.ru/DosrochkaOG.html

- Buzin A.Yu. Obraztsovyye vybory v Sochi [Model Election in Sochi]. – Website of Interregional Voter Association, 14.05.2009. URL: http://www.votas.ru/sochi2.html (accessed 17.05.2025). (In Russ.) - http://www.votas.ru/sochi2.html

- Ergebnisse nach Wahlbezirken. – Bundeswahlleiterin. URL: https://bundeswahlleiterin.de/dam/jcr/e79a7bd3-0607-4e87-9752-8e601e299e00/btw25_wbz.zip (accessed 17.05.2025). (In Ger.) - https://bundeswahlleiterin.de/dam/jcr/e79a7bd3-0607-4e87-9752-8e601e299e00/btw25_wbz.zip

- Lyubarev A. Zametki o vyborakh v bundestag – 2017. 3. Podrobneye o pochtovom golosovanii [Notes on the Bundestag Elections – 2017. 3. More on Postal Voting]. – Arkadii Lyubarev's LiveJournal, 02.10.2017. URL: https://lyubarev.livejournal.com/33213.html (accessed 17.05.2025). (In Russ.) - https://lyubarev.livejournal.com/33213.html

- Lyubarev A. Zametki o vyborakh v bundestag-2021, chast trerya. Pochtovoye golosovaniye v Saksonii [Notes on the Bundestag Elections-2021, Part Three. Postal Voting in Saxony]. – Arkadii Lyubarev's LiveJournal, 20.10.2021. URL: https://lyubarev.livejournal.com/101006.html (accessed 17.05.2025). (In Russ.) - https://lyubarev.livejournal.com/101006.html

- Yerygina V.I., Yerygin A.A. Golosovaniye po pochte kak vid distantsionnogo golosovaniya na vyborakh v organy publichnoi vlasti [Voting by Mail as a Type of Remote Voting in Elections to Public Authorities]. – Citizen. Elections. Authority. 2022. No. 4 (26). P. 83–90. (In Russ.)

- Zhavoronkov S.V., Kasyan A.S., Yanovsky K.E. What Happened to the "Torch of Liberty": Russia's Lessons to Learn From 3 November 2020. – Electoral Politics. 2021. No. 1 (5). P. 5. - https://electoralpolitics.org/en/articles/chto-sluchilos-s-fakelom-svobody-uroki-3-noiabria-2020-goda-dlia-rossii/